An EM.Terrano Primer

Modeling Wireless Propagation

Every wireless communication system involves a transmitter that transmits some sort of signal (voice, video, data, etc.), a receiver that receives and detects the transmitted signal, and a channel in which the signal is transmitted into the air and travels from the location of the transmitter to the location of the receiver. The channel is the physical medium in which the electromagnetic waves propagate. The successful design of a communication system depends on an accurate link budget analysis that determines whether the receiver receives adequate signal power to detect it against the background noise. The simplest channel is the free space. Real communication channels, however, are more complicated and involve a large number of wave scatterers. For example, in an urban environment, the obstructing buildings, vehicles and vegetation reflect, diffract or attenuate the propagating radio waves. As a result, the receiver receives a distorted signal that contains several components with different power levels and different time delays arriving from different angles.

The rapid growth of wireless communications along with the high costs associated with the design and deployment of effective wireless infrastructures underline a persistent need for computer aided communication network planning tools. The different rays arriving at a receiver location create constructive and destructive interference patterns. This is known as the multipath effect. This together with the shadowing effects caused by building obstructions lead to channel fading. The use of statistical models for prediction of fading effects is widely popular among communication system designers. These models are either based on measurement data or derived from simplistic analytical frameworks. The statistical models often exhibit considerable errors especially in areas having mixed building sizes. In such cases, one needs to perform a physics-based, site-specific analysis of the propagation environment to accurately identify and establish all the possible signal paths from the transmitter to the receiver. This involves an electromagnetic analysis of the scene with all of its geometrical and physical details.

EM.Terrano in a Nutshell

EM.Terrano is a physics-based, site-specific, wave propagation modeling tool that enables engineers to quickly determine how radio waves propagate in urban, natural or mixed environments. EM.Terrano's simulation engine is equipped with a fully polarimetric, coherent ray tracing solver based on the Shooting-and-Bouncing-Rays (SBR) method, which utilizes geometrical optics (GO) in combination with uniform theory of diffraction (UTD) models of building edges. EM.Terrano lets you analyze and resolve all the rays transmitted from one ore more signal sources, which propagate in a real physical site made up of buildings, terrain and other obstructing structures. EM.Terrano finds all the rays received by a receiver at a particular location in the physical site and computes their power levels, time delays, angles of arrival, etc. Using EM.Terrano you can examine connectivity of a communication link between any two points in a real specific propagation site.

Line-of-Sight vs. Multipath Propagation Channel

In a free-space line-of-sight (LOS) communication system, the signal propagates directly from the transmitter to the receiver without encountering any obstacles (scatterers). Free-space line-of-sight channels are ideal scenarios that can typically be used to model aerial or space communication system applications.

Click here to learn more about the theory of a Free-Space Propagation Channel.

In ground-based systems, the presence of the ground as a very large reflecting surface affects the signal propagation to a large extent. Along the path from a transmitter to a receiver, the signal may also encounter many obstacles and scatterers such as buildings, vegetation, etc. In an urban canyon environment with many buildings of different heights and other scatterers, a line of sight between the transmitter and receiver can hardly be established. In such cases, the propagating signals bounce back and forth among the building surfaces. It is these reflected or diffracted signals that are often received and detected by the receiver. Such environments are referred to as âmultipathâ. The group of rays arriving at a specific receiver location experience different attenuations and different time delays. This gives rise to constructive and destructive interference patterns that cause fast fading. As a receiver moves locally, the receiver power level fluctuates sizably due to these fading effects.

Link budget analysis for a multipath channel is a challenging task due to the large size of the computational domains involved. Typical propagation scenes usually involve length scales on the order of thousands of wavelengths. To calculate the path loss between the transmitter and receiver, one must solve Maxwell's equations in an extremely large space. Full-wave numerical techniques like the Finite Difference Time Domain (FDTD) method, which require a fine discretization of the computational domain, are therefore impractical for solving large-scale propagation problems. The practical solution is to use asymptotic techniques such as SBR, which utilize analytical techniques over large distances rather than a brute force discretization of the entire computational domain. Such asymptotic techniques, of course, have to compromise modeling accuracy for computational efficiency.

The SBR Method

EM.Terrano provides an asymptotic ray tracing simulation engine that is based on a technique known as Shooting-and-Bouncing-Rays (SBR). In this technique, propagating spherical waves are modeled as ray tubes or beams that emanate from a source, travel in space, bounce from obstacles and are collected by the receiver. As rays propagate away from their source (transmitter), they begin to spread (or diverge) over distance. In other words, the cross section or footprint of a ray tube expands as a function of the distance from the source. EM.Terrano uses an accurate equi-angular ray generation scheme to that produces almost identical ray tubes in all directions to satisfy energy and power conservation requirements.

When a ray hits an obstructing surface, one or more of the following phenomena may happen:

- Reflection from the locally flat surface

- Transmission through the locally flat surface

- Diffraction from an edge between two conjoined locally flat surfaces

Click here to learn more about the theory of SBR Method.

Pros and Cons of EM.Terrano's SBR Solver

EM.Terrano's SBR simulation engine utilizes an intelligent ray tracing algorithm that is based on the concept of k-dimensional trees. A k-d tree is a space-partitioning data structure for organizing points in a k-dimensional space. k-d trees are particularly useful for searches that involve multidimensional search keys such as range searches and nearest neighbor searches. In a typical large radio propagation scene, there might be a large number of rays emanating from the transmitter that may never hit any obstacles. For example, upward-looking rays in an urban propagation scene quickly exit the computational domain. Rays that hit obstacles on their path, on the other hand, generate new reflected and transmitted rays. The k-d tree algorithm traces all these rays systematically in a very fast and efficient manner. Another major advantage of k-d trees is the fast processing of multi-transmitters scenes.

EM.Terrano performs fully polarimetric and coherent SBR simulations with arbitrary transmitter antenna patterns. Its SBR simulation engine is a true asymptotic "field" solver. The amplitudes and phases of all the three vectorial field components are computed, analyzed and preserved throughout the entire ray tracing process from the source location to the field observation points. You can visualize the magnitude and phase of all six electric and magnetic field components at any point in the computational domain. In most scenes, the buildings and the ground or terrain can be assumed to be made of homogeneous materials. These are represented by their electrical properties such as permittivity εr and electric conductivity Ï. More complex scenes may involve a multilayer ground or multilayer building walls. In such cases, one can no longer use the simple reflection or transmission coefficient formulas for homogeneous medium interfaces. EM.Terrano calculates the reflection and transmission coefficients of multilayer structures as functions of incident angle, frequency and polarization and uses them at the respective specular points.

It is very important to keep in mind that SBR is an asymptotic electromagnetic analysis technique that is based on Geometrical Optics (GO) and the Uniform Theory of Diffraction (UTD). It is not a "full-wave" technique, and it does not provide a direct numerical solution of Maxwell's equations. SBR makes a number of assumptions, chief among them, a very high operational frequency such that the length scales involved are much larger than the operating wavelength. Under this assumed regime, electromagnetic waves start to behave like optical rays. Virtually all the calculations in SBR are based on far field approximations. In order to maintain a high computational speed for urban propagation problems, EM.Terrano ignores double diffractions. Diffractions from edges give rise to a large number of new secondary rays. The power of diffracted rays drops much faster than reflected rays. In other words, an edge-diffracted ray does not diffract again from another edge in EM.Terrano. However, reflected and penetrated rays do get diffracted from edges just as rays emanated directly from the sources do.

Building a Propagation Scene

A typical propagation scene in EM.Terrano consists of several elements. At a minimum, you need a transmitter (Tx) at some location to launch rays into the scene and a receiver (Rx) at another location to receive and collect the incoming rays. A transmitter and a receiver together make the simplest propagation scene, representing a free-space line-of-sight (LOS) channel. A transmitter is one of EM.Cube's several source types, while a receiver is one of EM.Cube's several observable types. A simpler source type is a Hertzian dipole representing an almost omni-directional radiator. A simpler observable is a field sensor that is used to compute the electric and magnetic fields on a specified plane.

An outdoor propagation scene may involve several buildings modeled by impenetrable surfaces and an underlying flat ground or irregular terrain surface. An indoor propagation scene may involve several walls modeled by thin penetrable surfaces, a ceiling and a floor arranged according to a certain building layout. You can also build mixed scenes involving both impenetrable and penetrable blocks. Your sources and observables can be placed anywhere in the scene. Your transmitters and receivers can be placed outdoors or indoors. A complete list of the various elements of a propagation scene is given in the Physical Structure section of EM.Terrano's Navigation Tree as follows:

- Impenetrable Surfaces: feature reflection and diffraction of impinging rays. Rays hit the facets of this type of blocks and bounce back, but they do not penetrate the object. It is assumed that the interior of such blocks or buildings are highly absorptive.

- Penetrable Volumes: feature reflection, transmission and diffraction of impinging rays. These blocks are used to model propagation inside general material media or fog, rain and vegetation.

- Penetrable Surfaces: feature reflection, transmission and diffraction of impinging rays. These blocks represent thin surfaces that are used to model the exterior and interior walls of buildings. Rays reflect off the surface of penetrable surfaces and diffract off their edges. They also penetrate the thin surface and continue their path in the free space on the other side of the wall.

- Terrain Surfaces: feature reflection and optional diffraction of impinging rays. These blocks are used to provide one or more impenetrable, ground surfaces for the propagation scene. Rays simply bounce off terrain objects.

- Base Points: are used to define transmitter and receiver locations in the scene.

Adding a New Scene Element

In EM.Terrano, the scene elements like buildings, terrain objects and based points are grouped together based on their type. All the objects listed under a particular impenetrable surface group in the navigation tree share the same material properties and color and texture. To define a new block group, follow these steps:

- Right click on the name of the element type in the navigation tree and select Insert New Block... A dialog for setting up the block properties opens up with a default color, texture and predefined material type (except for the case of a base point).

- Specify a name for the block group and select a color or texture.

- The electromagnetic model that determines ray-block interactions is specified under Interface Type or Surface Type. In most applications, you will use a standard materials with known electrical properties, i.e. Permittivity (εr) and Electric Conductivity (Ï). EM.Terrano does not handle magnetic materials.

- Click the OK button of the dialog to accept the changes and close it.

Once a new block node has been created on the navigation tree, it becomes the "Active" group of the project workspace, which is always displayed in bold letters. Then you can start drawing new objects under that node. Any block group can be made active by right clicking on its name in the navigation tree and selecting the Activate item of the contextual menu.

It is recommended that you first create block groups, and then draw new objects under the active block group. However, if you start a new EM.Terrano project from scratch, and start drawing a new object without having previously defined any block groups, a new default impenetrable surface group is created and added to the navigation tree to hold your new CAD object.

You can always change the properties of a block group later by accessing its property dialog from the contextual menu. You can also delete a block group with its objects at any time.

Computational Domain & Global Ground

The SBR simulation engine requires a finite computational domain. All the stray rays that hit the boundaries of this finite domain are terminated during the simulation process. Such rays exit the computational domain and travel to the infinity, with no chance of ever reaching any receiver in the scene. When you define a propagation scene with various elements like buildings, walls, terrain, etc., a dynamic domain is automatically established and displayed as a green wireframe box that surrounds the entire scene. Every time you create a new object, the domain is automatically adjusted and extended to enclose all the objects in the scene.

The size of the Ray domain is specified in terms of six Offset parameters along the ±X, ±Y and ±Z directions. The default value of all these six offset parameters is 10 project units. You can change them arbitrarily. After changing these values, use the Apply button to make the changes effective while the dialog is still open. You can change the size and color of the domain box through the Ray Domain Settings Dialog, which can be accessed in one of the following three ways:

- Click the Domain

button of the Simulation Toolbar.

button of the Simulation Toolbar.

- Select the Simulate > Computational Domain > Settings... item of the Simulate Menu.

- Right click on the Ray Domain item of the Navigation Tree and select Domain Settings...

- Use the keyboard shortcut Ctrl + A.

Most outdoor and indoor propagation scenes include a flat ground at their bottom, which bounces incident rays back into the scene. EM.Cube's Propagation Module provides a global flat ground at z = 0. The global ground indeed acts as an impenetrable surface that blocks the entire computational domain from the z = 0 plane downward. It is displayed as a translucent green plane at z = 0 extending downward. The color of the ground plane is always the same as the color of the ray domain. The global ground is assumed to be made of a homogeneous dielectric material with a specified permittivity εr and electric conductivity Ï. By default, a rocky ground is assumed with εr = 5 and Ï = 0.005 S/m. You can remove the global ground, in which case, you will have a free space scene. To disable the global ground, open up the Global Ground Settings Dialog, which can be accessed by right clicking on the Global Ground item in the Navigation Tree and selecting Global Ground Settings... Remove the check mark from the box labeled "Include Half-Space Ground (z<0)" to disable the global ground. This will also remove the green translucent plane from the bottom of your scene. You can also change the material properties of the global ground and set new values for the permittivity and electric conductivity of the impenetrable, half-space, dielectric medium. Do not forget to disable the global ground if you want to model a free space propagation scene.

Buildings, Terrain & Obstructing Blocks

Impenetrable, penetrable and terrain surfaces and penetrable volumes represent buildings, blocks or objects that obstruct the propagation of electromagnetic waves (rays) in the free space. What differentiates them is the types of physical phenomena that are used to model their interaction with the impinging rays. The field intensity, phase and power of the reflected and transmitted rays depend on the material properties of the obstructing surface. The specular surface can be modeled as a simple homogeneous dielectric half-space or as a multilayer structure. In that respect, the buildings, walls, terrain or even the global ground all behave in a similar way:

- They terminate an impinging ray and replace it with one or more new rays.

- They represent a specular interface between two media of different material compositions for calculating the reflection, transmission and possibly diffraction coefficients.

EM.Terrano has generalized the concept of Block as any object that obstructs and affects radio wave propagation. Rays hit the facets of a block and bounce off the surface of those facets or penetrate them and continue their propagation. Rays also get diffracted off the edges of these blocks.

In EM.Cube's Propagation Module, blocks are grouped together by the type of their interaction with rays. EM.Cube currently offers three types of blocks for use in a propagation scene:

- Impenetrable Surfaces: Rays hit the facets of this type of blocks and bounce back, but they do not penetrate the object. It is assumed that the interior of such blocks or buildings are highly absorptive.

- Penetrable Surfaces: These blocks represent thin surfaces that are used to model the exterior and interior walls of buildings based on the "Thin Wall Approximation". Rays reflect off the surface of penetrable surfaces and diffract off their edges. They also penetrate such thin surfaces and continue their paths on the other side of the wall.

- Terrain Surfaces: These blocks are used to provide one or more impenetrable, ground surfaces for the propagation scene. Rays simply bounce off terrain objects. The global ground acts as a flat super-terrain that covers the bottom of the entire computational domain.

EM.Cube's Propagation Module allows you to define block groups of each of the above three types. Each block group has the same color or texture and its members share the same material properties: permittivity εr and conductivity Ï. Also, all the penetrable surfaces belonging to the same block group have the same wall thickness. You can define many different block groups with certain properties and underneath each introduce many member objects with different geometrical shapes and dimensions. The table below summarizes the characteristics of each block type:

| Block Type | Physical Effects | Admissible Object Types |

|---|---|---|

| Impenetrable Surface | Reflection, Diffraction | All Solid & Surface CAD Objects |

| Penetrable Surface | Reflection, Diffraction, Transmission | All Solid & Surface CAD Objects |

| Terrain Surface | Reflection | Tessellated Objects Only |

Click here to learn more about Block Types.

Importing & Exporting Terrain Models

You can import two types of terrain in EM.Terrano. The first type is ".TRN" terrain file, which is EM.Terrano's native terrain format. It is a basic digital elevation map with a very simple ASCII data file format. The resolution of the terrain map in the X and Y directions is specified in meters as STEPS. The (x, y, z) coordinates of the terrain points are then listed one point per line. The other type of terrain format supported by EM.Cube is the standard 7.5min DEM file format with a .DEM file extension.

To import an external terrain model, first you have to create a terrain group node in the Navigation Tree. Right click on the name of the terrain group in the Navigation Tree and select either Import Terrain... or Import DEM File... A standard Windows Open Dialog opens up, with the file type set to .TRN or .DEM extensions, respectively. You can browse your folders and find the right terrain model file to import.

You can also export all the terrain objects in the project workspace as a terrain file with a .TRN file extension. You can even import a DEM terrain model from an external file and then save and export it as a native terrain (.TRN) file. To export the terrain, select File > Export... from EM.Terrano's File Menu. The standard Windows Save Dialog opens up with the default file type set to .TRN. Type in a name for your new terrain file and click the Save button to export the terrain data.

Moving Objects among Block Groups

You can move one or more selected objects at a time among different block groups. The objects can be selected either in the project workspace, or their names can be selected from the navigation tree. Right click on the highlighted selection and select Move To > Propagation > from the contextual menu. This opens up another sub-menu with a list of all the available block groups already defined in your EM.Terrano project. Select the desired block node, and all the selected objects will move to that block group. In the case of a multiple selection from the navigation tree using the keyboard's Shift Key or Ctrl Key, make sure that you continue to hold the keyboard's Shift Key or Ctrl Key down while selecting the destination block group's name from the contextual menu.

In a similar way, you can move one or more objects from an EM.Terrano block group to one of EM.Cube's other modules. In this case, the sub-menus of the Move To > item of the contextual menu will indicate all the EM.Cube modules that have valid groups for transfer of the selected objects. You can also move one or more objects from EM.Cube's other modules to a block group in EM.Terrano.

| |

Except for external terrain models, you can import other external objects (STEP, IGES, STL, etc.) only to CubeCAD. You need to move the imported objects form CubeCAD to EM.Terrano as described above. |

Defining Sources & Observables

Like every other electromagnetic solver, EM.Terrano's SBR ray tracer requires a source for excitation and one or more observables for generation of simulation data. EM.Terrano offers several types of sources and observables for a SBR simulation. You can mix and match different source types and observable types depending on the requirements of your modeling problem. There are two types of sources:

There are four types of observables:

- Receiver

- Field Sensor

- Far Field Radiation Pattern

- Huygens Surface

Using EM.Terrano as a Field Solver

The simplest SBR simulation can be performed using a short dipole source with a specified field sensor plane. As an asymptotic EM solver, EM.Terrano then computes the electric and magnetic fields radiated by your dipole source in the presence of your multipath propagation environment. EM.Terrano's short dipole source and field sensor observable are very similar to those of EM.Cube's other computational modules. You can also compute the far field radiation patterns of a dipole in the presence of surrounding scatterers or compute the Huygens surface data for use in EM.Cube's other modules.

Click here to learn more about using EM.Terrano as a Asymptotic Field Solver.

Defining Base Point Sets

Transmitters and receivers are more complicated source and observable types that can be used to model more realistic communication links. A conventional urban propagation scene can be set up using a transmitter and an array of receivers. In order to tie up transmitters and receivers with CAD objects in the project workspace, EM.Terrano uses point objects to define transmitters and receivers. These point objects represent the base of the location of transmitters and receivers in the computational domain. Hence, they are grouped together as "Base Sets". You can easily interchange the role of transmitters and receivers in a scene by switching their associated bases. The usefulness of concept of base sets will become apparent later when you place transmitters or receivers on an irregular terrain and adjust their elevation.

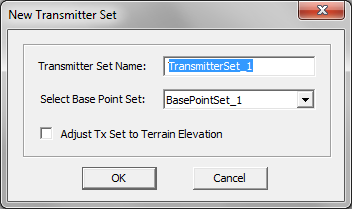

To create a new base set, right click on the Base Sets item of Navigation Tree and select Insert Base Set... A dialog for setting up the Base Set properties opens up.

- Enter a name for the base set and change the default blue color if you wish. It is useful to differentiate the base sets associated with transmitters and receivers by their color.

- Click the OK button to close the Base Set Dialog.

Once a base set node has been added to the Navigation Tree, it becomes the active node for new object drawing. Under base sets, you can only draw point objects. All other object creation tools are disabled. A point is initially drawn on the XY plane. Make sure to change the Z-coordinate of your radiator, otherwise, it will fall on the global ground at z = 0. You can also create arrays of base points under the same base set. This is particularly useful for setting up receiver grids to compute coverage maps. Simply select a point object and click the Array Tool of Tools Toolbar or use the keyboard shortcut "A". Enter values for the X, Y or Z spacing as well as the number of elements along these three directions in the Array Dialog. In most propagation scenes you are interested in 2D horizontal arrays along a fixed Z coordinate (parallel to the XY plane).

Defining Transmitter Sets

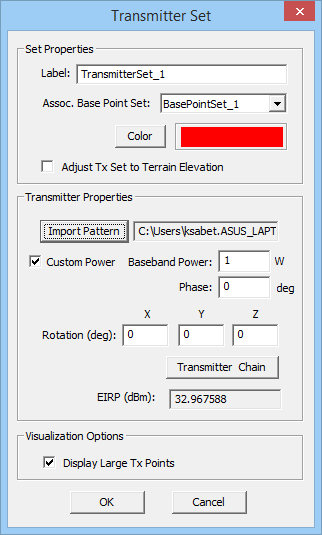

A short dipole is the closest thing to an omni-directional radiator. The direction or orientation of the short dipole determines its polarization. In many applications, you may rather want to use a directional antenna for your transmitter. You can model a radiating structure using EM.Cube's FDTD, Planar, MoM3D or PO modules and generate a 3D radiation pattern data file for it. These data are stored in a specially formatted file with a ".RAD" extension, which contains columns of spherical Ï and θ angles as well as the real and imaginary parts of the complex-valued far field components Eθ and EÏ. The θ- and Ï-components of the far-zone electric field determine the polarization of the transmitting radiator.

To define a directional transmitter radiator, you need to select the "User Defined" option in the "Radiator" section of the Transmitter Dialog. You can do this either at the time of creating a transmitter set, or afterwards by opening the property dialog of the transmitter set. In the "Custom Pattern Parameters", click the Import Pattern button to set the path for the radiation data file. This opens up the standard Windows Open dialog, with the default file type or extension set to ".RAD". Browse your folders to find the right data file. A radiation pattern file usually contains the value of "Total Radiated Power" in its file header. This is used by default for power calculations in the SBR simulation. However, you can check the box labeled "Custom Power" and enter a value for the transmitter power in Watts. EM.Cube can also rotate the imported radiation pattern arbitrarily. In this case, you need to specify the Rotation angles in degrees about the X-, Y- and Z-axes. Note that these rotations are performed sequentially and in order: first a rotation about the X-axis, then a rotation about the Y-axis, and finally a rotation about the Z-axis.

Figure 1: Propagation Module's Transmitter dialog with a user defined radiator selected.

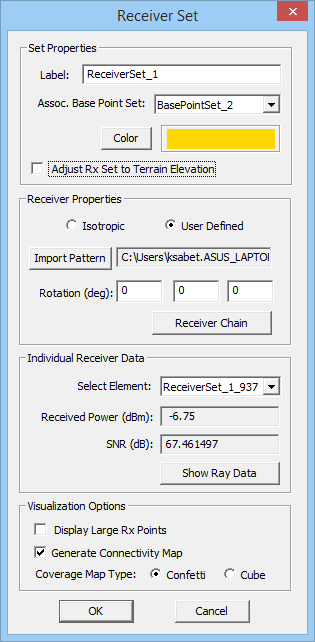

Defining Receiver Sets

Receivers act as observables in a propagation scene. The objective of a SBR simulation is to calculate the far-zone electric fields and the total received power at the location of a receiver. In that sense, receivers indeed act as field observation points. You need to define at least one receiver in the scene before you can run a SBR simulation. You define the receivers of your scene by associating them with the base sets you have already defined in the project workspace. Unlike transmitters that usually one or few, a typical propagation scene may involve a large number of receivers. To generate a wireless coverage map, you need to define an array of points as your base set.

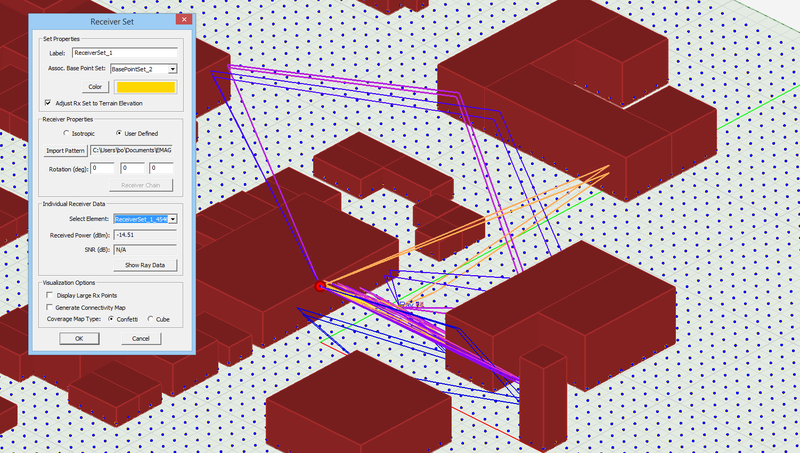

To define a new Receiver Set, go to the Observables section of the Navigation Tree, right click on the Receivers item and select Insert Receiver... A dialog opens up that contains a default name for the new Receiver Set as well as a dropdown list labeled Select Radiator Set. In this list you will see all the available base sets that you have already define in the project workspace. Select and designate the desired base set as the receiver set. Note that if the base set contains more than one point, all of them are designated as receivers. After defining a receiver set, the points change their color to the receiver color, which is yellow by default. The first element of the set is represented by a larger ball of the same color indicating that it is the selected receiver in the scene. The Receiver Set Dialog is also used to access individual receivers of the set for data visualization at the end of a simulation. At the end of an SBR simulation, the button labeled "Show Ray Data" becomes enabled. Clicking this button opens the Ray Data Dialog, where you can see a list of all the received rays at the selected receiver and their computed characteristics.

Figure 1: Propagation Module's Receiver dialog.

Adjustment of Transmitter & Receiver Elevation above a Terrain Surface

In EM.Cube, all the transmitters and receivers are tied up with point objects in the project workspace. These point objects are grouped and organized in base sets. When you move the point objects or change their coordinates, all of their associated transmitters or receivers immediately follow them to the new location. For example, you usually define a grid of receivers using a base set that is made up of a uniformly spaced array of points and spread them in your scene. All of these receivers have the same height because their associated base points all have the same Z-coordinate. When your receivers are located above a flat terrain like the global ground, their Z-coordinates are equal to their height above the ground, as the terrain elevation is fixed and equal to zero everywhere. The same is true for transmitters, too.

In many propagation modeling problems, your transmitters and receivers may be located above an irregular terrain with varying elevation across the scene. In that case, you may want to place your transmitters or receivers at a certain height above the underlying ground. The Z-coordinate of a transmitter or receiver is now the sum of the terrain elevation at the base point and the specified height. EM.Cube gives you the option to adjust the transmitter and receiver sets to the terrain elevation. This is done for individual transmitter sets and individual receiver sets. At the top of the Transmitter Dialog there is a check box labeled "Adjust Tx Sets to Terrain Elevation". Similarly, at the top of the Receiver Dialog there is a check box labeled "Adjust Rx Sets to Terrain Elevation". These boxes are unchecked by default. As a result, your transmitter sets or receiver sets coincide with their associated base points in the project workspace. If you check these boxes and place a transmitter set or a receiver set above an irregular terrain, the transmitters or receivers are elevated from the location of their associated base points by the amount of terrain elevation as can be seen in the figure below.

To better understand why there are two separate sets of points in the scene, note that a point array (CAD object) is used to create a uniformly spaced base set. The array object always preserves its grid topology as you move it around the scene. However, the transmitters or receivers associated with this point array object are elevated above the irregular terrain and no longer follow a strictly uniform grid. If you move the base set from its original position to a new location, the base points' topology will stay intact, while the associated transmitters or receivers will be redistributed above the terrain based on their new elevations.

Running A SBR Simulation

Discretizing the Scene

In a typical SBR simulation, a ray is traced from the location of the source until it hits a scatterer. The SBR method assumes that the ray hits either a flat facet of the scatterer or one of its edges. In the case of hitting a flat facet, the specular point is used to launch new reflected and transmitted rays. The surface of the facet is treated as an infinite dielectric medium interface, at which the reflection and transmission coefficients are calculated. In the case of hitting an edge, new diffracted rays are generated in the scene. However, only those who reach a nearby receiver in their line of sight are ever taken into account. In other words, diffractions are treated locally.

EM.Cube's Propagation Module allows you to draw any type of surface or solid CAD objects under impenetrable and penetrable surface groups. Some of these objects have flat faces such as boxes, pyramids, rectangle or triangle strips, etc. Some others contain curved surfaces or curved boundaries such as cylinders, cones, etc. All the non-flat surfaces have to be discretized in the form of a collection of smaller flat facets. EM.Cube uses a triangular surface mesh generator to discretize the penetrable and impenetrable surface objects of your propagation scene. This mesh generator is very similar to the ones used in EM.Cube's two other modules: MoM3D and Physical Optics (PO).

You can build a variety of surface and solid objects using EM.Cube's native "Curve" CAD objects like lines, polylines, circles, etc. You can use tools like Extrude, Loft, Strip-Sweep, Pipe-Sweep, etc. to transform curves into surface or solid objects. However, keep in mind that all the "Curve" CAD objects are ignored by the SBR mesh generator and are therefore not sent to the simulation engine.

Special Discretized Object Types

In EM.Cube, terrain objects are represented by and saved as special "Tessellated" objects with quadrilateral cells. This is true of terrain objects that you create yourself using EM.Cube's Terrain Generator as well as all the terrain objects that you import from external files to your project. The center of each cell represents the terrain elevation at that point. Tessellated objects are considered as discretized objects by EM.Cube and they are not meshed one more time by the SBR mesh generator. Each quadrilateral cell is divided into two triangular cells before being passed to the SBR simulation engine. Therefore, when using EM.Cube's Terrain Generator to create a new terrain object, you have to pay special attention to the resolution of the terrain object as it determines the total number of terrain facets sent to the simulation engine. A high resolution terrain, although looking better and more realistic, may easily lead to an enormous computational problem.

You can use EM.Cube's "Polymesh" tool to discretize solid and surface CAD objects. You can manually control the mesh characteristics of polymesh objects including inserting new nodes on faces and edges or deleting existing nodes. In addition, EM.Cube's Solid Generator and Surface Generator tools create ploymesh solids and surfaces, respectively. Like tessellated object, polymesh objects are also considered as discretized objects by EM.Cube and they are not meshed again by the SBR mesh generator.

Viewing SBR Mesh

You can view and examine the discretized version of your scene objects as they are sent to the SBR simulation engine. To view the mesh, click the Mesh ![]() button of the Simulate Toolbar or select Simulate > Discretization > Show Mesh, or use the keyboard shortcut Ctrl+M. A triangular surface mesh of your physical structure appears in the project workspace. In this case, EM.Cube enters it mesh view mode. You can perform view operations like rotate view, pan, zoom, etc. But you cannot select objects, or move them or edit their properties. To get out of the Mesh View and return to EM.Cube's Normal View, press the Esc Key of the keyboard, or click the Mesh button of the Simulate Toolbar once again, or go to the Simulate Menu and deselect the Discretization > Show Mesh item.

button of the Simulate Toolbar or select Simulate > Discretization > Show Mesh, or use the keyboard shortcut Ctrl+M. A triangular surface mesh of your physical structure appears in the project workspace. In this case, EM.Cube enters it mesh view mode. You can perform view operations like rotate view, pan, zoom, etc. But you cannot select objects, or move them or edit their properties. To get out of the Mesh View and return to EM.Cube's Normal View, press the Esc Key of the keyboard, or click the Mesh button of the Simulate Toolbar once again, or go to the Simulate Menu and deselect the Discretization > Show Mesh item.

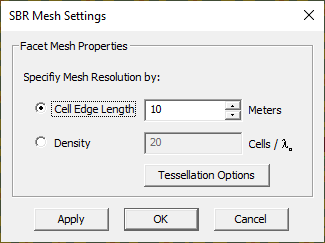

You can adjust the mesh resolution and increase the geometric fidelity of discretization by creating more and finer triangular facets. On the other hand, you may want to reduce the mesh complexity and send to the SBR engine only a few coarse facets to model your buildings. To adjust the mesh resolution, open the Mesh Settings Dialog by clicking the Mesh Settings ![]() button of the Simulate Toolbar or select Simulate > Discretization > Mesh Settings.... This dialog provides a single parameters: Edge Length., which has a default value of 100 project units. If you are already in the Mesh View Mode and open the Mesh Settings Dialog, you can see the effect of changing the edge length using the Apply button. Click OK to close the dialog.

button of the Simulate Toolbar or select Simulate > Discretization > Mesh Settings.... This dialog provides a single parameters: Edge Length., which has a default value of 100 project units. If you are already in the Mesh View Mode and open the Mesh Settings Dialog, you can see the effect of changing the edge length using the Apply button. Click OK to close the dialog.

Note that unlike EM.Cube's other computational modules that express the default mesh density based on the wavelength, the resolution of the SBR mesh generator is expressed in project length units. The default edge length value of 100 units might be too large for non-flat objects. You may have to use a lower value to capture the curvature of your curved structures adequately.

Figure 1: Propagation Module's Mesh Settings dialog.

SBR Simulation Types

EM.Cube's Propagation Module offers three types of ray tracing simulations:

- Analysis

- Frequency Sweep

- Parametric Sweep

An SBR analysis is the simplest ray tracing simulation and involves the following steps:

- Set the unit of project scene and the frequency of operation. Note that EM.Cube's default project unit is millimeter. When working with the Propagation Module, pay attention to the project unit. Radio propagation problems usually require meter, mile or kilometer as the project unit.

- Create the blocks and draw the buildings at the desired locations.

- Keep the default ray domain and accept the default global ground or change its material properties.

- Define the base sets (at least one for the transmitter and one for the receiver).

- Define the transmitter and receiver(s) using the available base sets.

- Run the SBR simulation engine.

- Visualize the coverage map and plot other data.

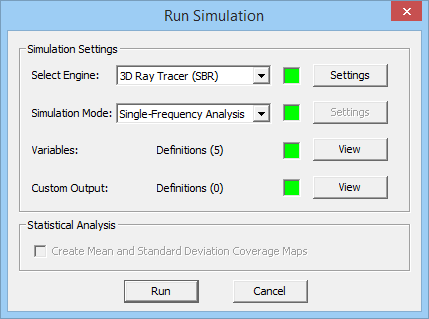

You can access the Propagation Module's run dialog by clicking the Run ![]() button of the Simulate Toolbar or by selecting Simulate > Run... or using the keyboard shortcut Ctrl+R. When you click the Run button, a new window opens up that reports the different stages of the SBR simulation and indicates the progress of each stage. After the SBR simulation is successfully completed, a message pops up and prompts the completion of the process.

button of the Simulate Toolbar or by selecting Simulate > Run... or using the keyboard shortcut Ctrl+R. When you click the Run button, a new window opens up that reports the different stages of the SBR simulation and indicates the progress of each stage. After the SBR simulation is successfully completed, a message pops up and prompts the completion of the process.

Figure 1: Propagation Module's Simulation Run dialog.

SBR Simulation Parameters

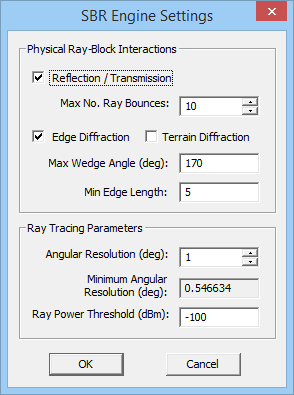

There are a number of SBR simulation settings that can be accessed and changed from the SBR Settings Dialog. To open this dialog, click the button labeled Settings on the right side of the Select Engine dropdown list in the Run Dialog. EM.Cube's SBR simulation engine allows you to separate the physical effects that are calculated during a ray tracing process. You can selectively enable or disable Ray Reflection, Ray Transmission and Ray Diffraction. By default, all three effects are checked and included in the computations. Separating these effects sometimes help you better analyze your propagation scene and understand the impact of various blocks in the scene.

EM.Cube requires a finite number of ray bounces for each original ray emanating from a transmitter. This is very important in situations that may involve resonance effects where rays get trapped among certain group of surfaces and may bounce back and forth indefinitely. This is set using the box labeled "Max No. Ray Bounces", which has a default value of 10. Note that the maximum number of ray bounces directly affects the computation time as well as the size of output simulation data files. This can become critical for indoor propagation scenes, where most of the rays undergo a large number of reflections.

As rays travel in the scene and bounce from surfaces, they lose their power and their amplitudes diminish. From a practical point of view, only rays that have power above the receiver sensitivity threshold can be effectively received. Therefore, all the rays whose power fall below a specified power threshold are discarded. The Ray Power Threshold is specified in dBm and has a default value of -100dBm. Keep in mind that the value of this threshold directly affects the accuracy of the simulation results as well as the size of the output data file.

You can also set the Angular Resolution of the transmitter rays in degrees. By default, every transmitter emanates equi-angular ray tubes at a resolution of 1 degree. Lower angular resolutions larger than 1° speed up the SBR simulation significantly, but they may compromise the accuracy. Higher angular resolutions less than 1° increase the accuracy of the simulating results, but they also increase the computation time.

Figure 1: Propagation Module's SBR Engine Settings dialog.

The Coverage Map

If the associated radiator set is isotropic, so will be the transmitter set. By default, an isotropic transmitter has vertical polarization. You can use the Polarization radio button to select one of the two options: Vertical or Horizontal. If the associated radiator set consists of Short Dipole or User Defined radiators, it is indicated in the transmitter property dialog. In the case of a short dipole radiator, you can set a value for the dipole current in Amperes. The radiation resistance of a short dipole of length dl is given by:

- [math] R_r = 80\pi^2 \left( \frac{dl}{\lambda_0} \right)^2 [/math]

The radiated power of a short dipole carrying a current I0 is then given by:

- [math] P_{rad} = \frac{1}{2} R_r |I_0|^2 = 40\pi^2 |I_0|^2 \left( \frac{dl}{\lambda_0} \right)^2 [/math]

For isotropic and user defined radiators you can set the Input Power and Phase of a transmitter set in Watts and degrees, respectively. This can be accessed from the Transmitter Chain dialog, which will be described in detail in the next section. The radiation pattern of the associated radiator set is normalized and used in conjunction with the input power value to create a weighted distribution of transmitted rays. In certain cases like hybrid simulations, you may want to use the actual values of the far field to define the transmitter power rather than a normalized radiation pattern. Note that the pattern (.RAD) file contains the value of total radiated power in its header. In this case, check the box labeled "Calculate Power From Radiation Pattern". This is calculated directly from the complex θ and Ï components of the far field data by integrating them over the entire space (4Ï solid angle). Note that this option is available only when the radiator is of the User Defined type. When this box is checked, the transmitter chain button is grayed out. By default, an isotropic transmitter emanates rays uniformly in all directions at the angular resolution specified by the user. A transmitter with a user defined associated radiator may represent a highly directional radiation pattern with the main beam pointing in a certain direction. You can additionally force and limit the Angular Extents of rays to a certain solid angle around the transmitter. This is especially useful and computationally efficient when the transmitter is on one side of the scene, and all the scatterers and receivers are on the other side. In this case, there is no need to generate rays in all directions. To limit the angular extents of rays, define the Start and End values for both Theta (θ) and Phi (Ï) angles. The value of the angular resolution of the rays can be changed from the Run Dialog as will be discussed later.

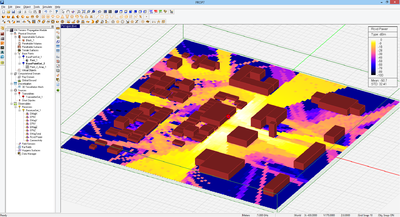

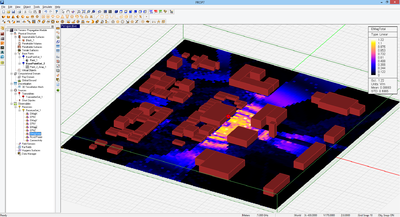

In a regular SBR simulation, you have a transmitter and one or more arrays of receivers in your scene. At the end of the simulation, you can visualize the coverage map of the transmitter over the receiver sets. A coverage map shows the total Received Power by each of the receivers and is visualized as a color-coded intensity plot. You can visualize the coverage maps of individual receiver sets. At the end of a SBR simulation, each Received Power Coverage Map is listed under the receiver set's name in the Navigation Tree. To display a coverage map, simply click on its entry in the Navigation Tree. The coverage map plot appears in the Main Window overlaid on the scene. A legend box on the right shows the color scale and units (dB). The 3-D coverage maps are displayed as horizontal confetti above the receivers. If the receivers are packed close to each other, you will see a continuous confetti map. If the receivers are far apart, you will see individual colored squares. You can also visualize coverage maps as colored 3-D cubes. This may be useful when you set up your receivers in a vertical arrangement or the scene has a highly uneven terrain. To change the type of coverage map visualization, open the receiver set's property dialog and select the desired option for Coverage Map: Confetti or Cube in the "Visualization Options" section of the dialog.

Figure: Received power coverage map: (Left) confetti style, and (Right) cube style.

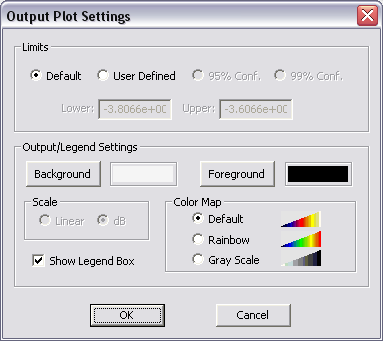

You can change the settings of the coverage map by right clicking on its entry in the Navigation Tree and selecting Properties... or by double-clicking on the legend box. In the Output Plot Settings dialog, you can choose from one of three Color Map options: Default, Rainbow and Grayscale. The visualization plot uses default values for the color scale. In the section titled "Limits", you can choose the radio button labeled User Defined. Then, you have to enter new values for the Lower and Upper Limits of the plot. You can also show or hide the Legend Box or change its Background and Foreground colors by clicking the buttons provided for this purpose.

Output Plot Settings

The Ray Data

At the end of a SBR simulation, each receiver receives a number of rays. Some receivers may not receive any rays at all. You can visualize all the rays received by a certain receiver from the active transmitter of the scene. To do this, right click the Receivers item of the Navigation Tree. From the context menu select Show Received Rays. All the rays received by the currently selected receiver of the scene are displayed in the scene. The rays are identified by labels, are ordered by their power and have different colors for better visualization. You can display the rays for only one receiver at a time. The receiver set property dialog has a list of all the individual receivers belonging to that set. To display the rays received by another receiver, you have to change the Selected Receiver in the receiver set's property dialog. If you keep the mouse focus on this dropdown list and roll your mouse scroll wheel, you can scan the selected receivers and move the rays from one receiver to the next in the list. To remove the visualized rays from the scene, right click the Receivers item of the Navigation Tree again and from the context menu select Hide Received Rays.

Visualization of received rays at the location of the selected receiver.

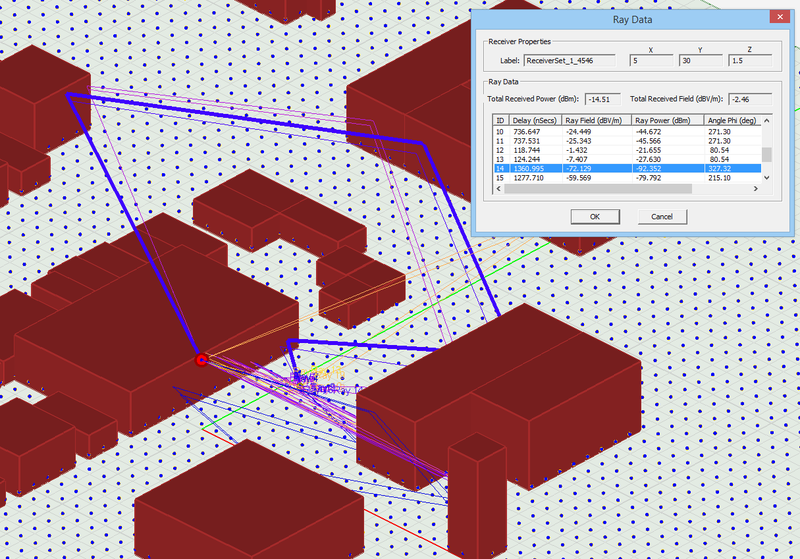

You can also view the ray parameters by opening the property dialog of a receiver set. By default, the first receiver of the set is always selected. You can select any other receiver from the drop-down list labeled Selected Receiver. If you click the button labeled Show Ray Data, a new dialog opens up with a table that contains all the received rays at the selected receiver and their parameters:

- Delay is the total time delay that a ray experiences travelling from the transmitter to the receiver after all the reflections, transmissions and diffractions and is expressed in nanoseconds.

- Ray Field is the received electric field at the receiver location due to a specific ray and is given in dBV/m.

- Ray Power is the received power at the receiver due to a specific ray and is given in dBm.

- Angles of Arrival are the θ and Ï angles of the incoming ray at the local spherical coordinate system of the receiver.

The Ray Data Dialog also shows the Total Received Power in dBm and Total Received Field in dBV/m due to all the rays received by the receiver. You can sort the rays based on their delay, field, power, etc. To do so, simply click on the grey column label in the table to sort the rays in ascending order based on the selected parameter. You can also select any ray by clicking on its ID and highlighting its row in the table. In that case, the selected rays is highlighted in the Project Workspace and all the other rays become thin (faded).

Note: The rays are summed up coherently at the receiver.

Figure: Analyzing a selected ray from the ray data dialog.

Plotting Other Simulation Results

Besides visualizing the coverage map and received rays in the EM.CUBE's Propagation Module, you can also plot the Path Loss of all the receivers belonging to a receiver set as well as the Power Delay Profile of individual receivers. To plot these data, go the Observables section of the Navigation Tree and right click on the Receivers item. From the context menu, select Plot Path Loss or Plot Power Delay Profile, respectively. The path loss data between the active transmitter and all the receivers belonging to a receiver set are plotted on a Cartesian graph. The horizontal axis of this graph represents the index of the receiver. Power Delay Profile is a bar chart that plots the power of individual rays received by the currently selected receiver versus their time delay. If there is a line of sight (LOS) between a transmitter and receiver, the LOS ray will have the smallest delay and therefore will appear first in the bar chart. Sometimes you may have several rays arriving at a receiver at the same time, i.e. all with the same delay, but with different power level. These will appear as stacked bars in the chart.

You can also plot the path loss and power delay profile graphs and many others from EM.CUBE's data manager. You can open data manager by clicking the Data Manager ![]() button of the Compute Toolbar or by selecting Compute

button of the Compute Toolbar or by selecting Compute ![]() Data Manager from the menu bar or by right clicking on the Data Manager item of the Navigation Tree and selecting Open Data Manager... from the contextual menu or by using the keyboard shortcut Ctrl+D. In the Data manager Dialog, you will see a list of all the data files available for plotting. These include the theta and phi angles of arrival and departure of the selected receiver. You can select any data file by clicking and highlighting its ID in the table and then clicking the Plot button.

Data Manager from the menu bar or by right clicking on the Data Manager item of the Navigation Tree and selecting Open Data Manager... from the contextual menu or by using the keyboard shortcut Ctrl+D. In the Data manager Dialog, you will see a list of all the data files available for plotting. These include the theta and phi angles of arrival and departure of the selected receiver. You can select any data file by clicking and highlighting its ID in the table and then clicking the Plot button.

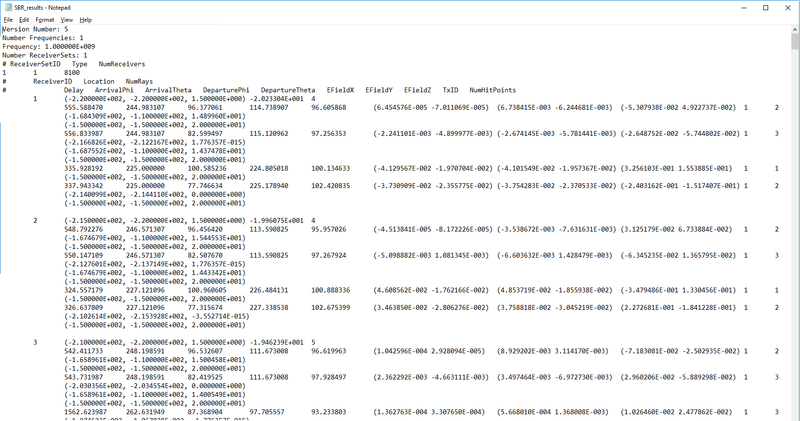

Output Data Files

At the end of an SBR simulation, the results are written into a main output data file with the reserved name of SBR_Results.RTOUT. This file has the following format:

NEW LINE:

- Receiver Number

- Receiver Base X, Y , Z Coordinates

- Receiver Height

NEW LINE:

Number of Rays

NEW LINE:

- Ray Number

- θ and Ï Angles of Arrival in deg

- θ and Ï Angles of Departure in deg

- Delay in nsec

- Real(EV) & Imag(EV)

- Real(EH) & Imag(EH)

- Real(E.eR) & Imag(E.eR)

- Power

The angles of arrival are the θ and Ï angles of a received ray measured in degrees and are referenced in the spherical coordinate systems centered at the location of the receiver. The angles of departure for a received ray are the θ and Ï angles of the originating transmitter ray, measured in degrees and referenced in the spherical coordinate systems centered at the location of the active transmitter, which eventually arrives at the receiver. The total time delay is measured in nanoseconds between t = 0 nsec at the time of launch from the transmitter location till being received at the receiver location. The last four columns show the real and imaginary parts of the received electric fields with vertical and horizontal polarizations, respectively. The complex field values are normalized in a way that when their magnitude is squared, it equals the received ray power. If the active transmitter is an isotropic radiator with either a vertical or horizontal polarization, then the field components corresponding to the other polarization will have zero entries in the output data file.

Figure: A typical SBR output data file.

Running A Frequency Sweep With SBR

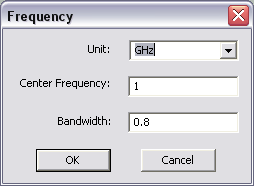

By default, you run a single-frequency simulation in EM.CUBE's Propagation Module. You set the operational frequency of a SBR simulation in the project's Frequency Dialog, which can be accessed in a number of ways:

- By clicking the Frequency

button of the Compute Toolbar.

button of the Compute Toolbar.

- By selecting Compute

Frequency Settings... from the Menu Bar.

Frequency Settings... from the Menu Bar.

- Using the keyboard shortcut Ctrl+F.

- By double clicking the frequency section (box) of the Status Bar.

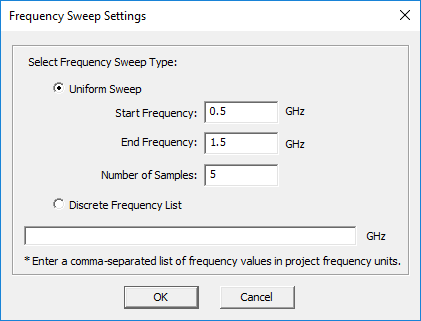

(Left) Project's frequency dialog and (Right) the frequency settings dialog.

You can also select the Frequency Sweep option in the Simulation Mode drop-down list of the Run Dialog. Click the Settings... button on the right side of this dropdown list to open up the Frequency Settings Dialog. Based on the original values of the project center frequency and bandwidth, the Start Frequency and End Frequency have default values. You can also change the Number of Samples. Once you click the Run button, EM.CUBE performs a frequency sweep by assigning each of the frequency samples as the current operational frequency and running the SBR simulation engine at that frequency. All the simulation data at all frequency samples are saved into the output data files including "SBR_results.RTOUT". After the completion of a frequency sweep simulation, as many coverage maps as the number of frequency samples are generated and added to the Navigation Tree under the Receiver Set's entry. You can click on each of the coverage maps corresponding to each of the frequency samples and visualize it in the project workspace. You can also animate the coverage maps. To do so, right click on the receiver set's name in the Navigation Tree and select Animation from the contextual menu. The coverage maps start to animate by their order on the Navigation Tree. Once the entire list is displayed sequentially, it starts all over again from the beginning of the list. During the animation, the Animation Controls dialog appears at the lower right corner of the screen. This dialog has a number of buttons for pause/resume, step forward/backward, and step to the end/start. The title of each coverage map is shown in the box labeled Sample as it is displayed in the main window. You can also change the speed of animation. The default frame duration has a value of 300 (3x100) milliseconds. To stop the animation, simply press the keyboard's Esc Key.

Multiple coverage maps on the Navigation Tree at the end of a frequency sweep and starting an animation from the contextual menu.

Animation controls dialog in the project workspace.

Running a Parametric Sweep with SBR

In EM.CUBE, all the CAD object properties as well as certain source, material and mesh parameters can be assigned as variables. Variables are defined to control and vary the values of such parameters either for editing purposes or to run parametric sweep or optimization. Variable are defined using the Variables Dialog, which can be accessed in the three ways:

- By clicking the Variables

button of the Compute Toolbar.

button of the Compute Toolbar.

- By selecting Compute

Variables... from the Menu Bar.

Variables... from the Menu Bar.

- Using the keyboard shortcut Ctrl+B.

The variables dialog is initially empty. To add a new variable, click the Add button to open up the Add Variable/Syntax Dialog. In this dialog you have to type in a name for the new variable and choose a type. The default type is Uniformly Spaced Samples. You also need to specify the Start, Stop and Step values for the variable. In the figure below, a variable called "Tx_Height" is defined that varies between 2 and 10 with equal steps of 2. This means the sample set {2,4,6,8,10}. When you return to the variables dialog, the syntax of the new variable is shown as 2:10:2. The last number in this syntax is always the variable step. In this example, this variable is going to be used to control the height of the transmitter in a propagation scene.

Next, you have to attach the variable to the CAD object. In this case, the CAD object is the point object that represents the transmitter's radiator. To attach a variable to a CAD object, open the object's property dialog and type in the name of the variable as the value of a property or parameter. In this case, the variable Tx_Height is going to control the Z-Coordinate of the point object. Once the value of the object parameter is replaced by the name of an already defined variable, it is updated with the current value of that variable. In the case of a variable of "Uniformly Spaced Samples" type, the current value is the start value. This value will be incrementally varied during a parametric sweep simulation process. Note that a variable can take a fixed value or a discrete set of values, too. You can always open the variables dialog and change the value or syntax of any variable. To make a new or modified value effective, click the Apply button of the variables dialog. You can test the values by performing a Dry Run of the selected variable. This runs an animation of the project workspace as the value of the variable changes and all the related CAD objects are updated accordingly. Note that you can attach the same variable to more than one CAD object property or to the properties of different objects. You can also define multiple values or syntaxes to the same variable. To do so, open the Add Variable/Syntax Dialog, and instead of typing in a new variable name, choose an existing variable name from the Name dropdown list. This will add a new value or syntax to the existing syntax(es) of the selected variable. When you return to the variables dialog, variables with more than one value or syntax will have a dropdown list in the Syntax column. You can choose any of these values or syntaxed at any time and make the change effective by clicking the Apply button.

Replacing the value of a CAD object parameter with a variable name.

To run a parametric sweep, open the Run Dialog and select the Parametric Sweep option in the Simulation Mode drop-down list. If you have not defined any variables in the project, the box in the Variables row before the View will be red. You have to turn it into green before you can run a simulation. By clicking the View button, you can open up the variables dialog from here. Once you click the Run button, EM.CUBE performs a parametric sweep by incrementally varying the values of all the defined variables from their start to stop values at the specified steps and updating all the related CAD objects. After the completion of a parametric sweep simulation, as many coverage maps as the total number of variable samples are generated and added to the Navigation Tree under the receiver set's entry. You can click on each of the coverage maps and visualize it in the project workspace. You can also animate the coverage maps sequentially. To do so, right click on the receiver set's name in the Navigation Tree and select Animation from the contextual menu. To stop the animation, simply press the keyboard's Esc Key.

Choosing parametric sweep as the simulation mode in the run dialog. Note that one variable has been defined and EM.CUBE is ready to run the simulation.

The coverage map of the scene at the end of a parametric sweep where the sweep variable is the transmitter height.

Statistical Analysis of Propagation Scene

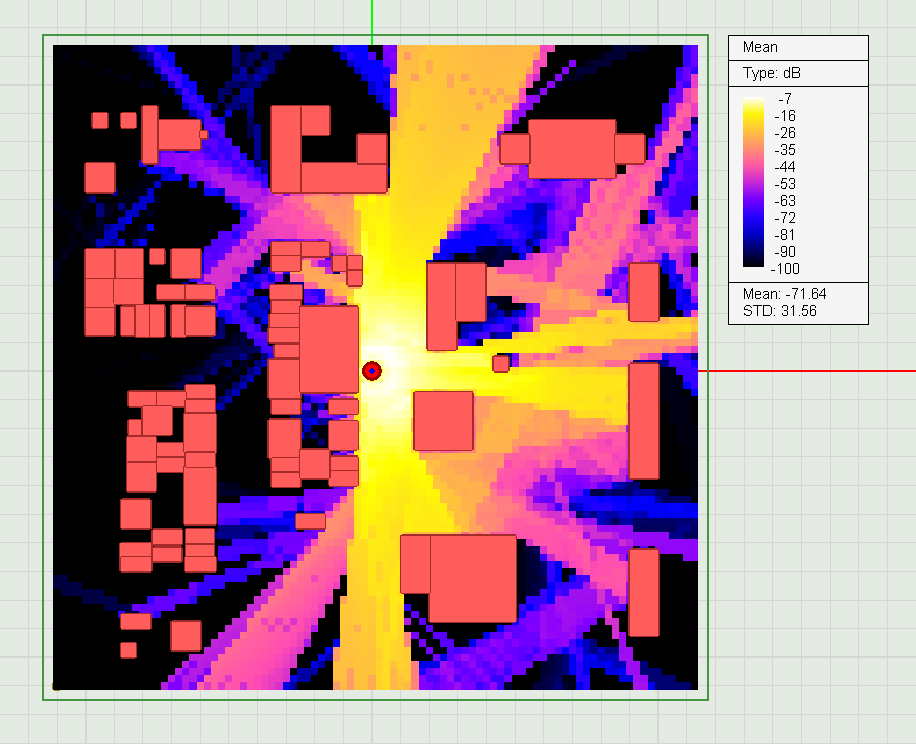

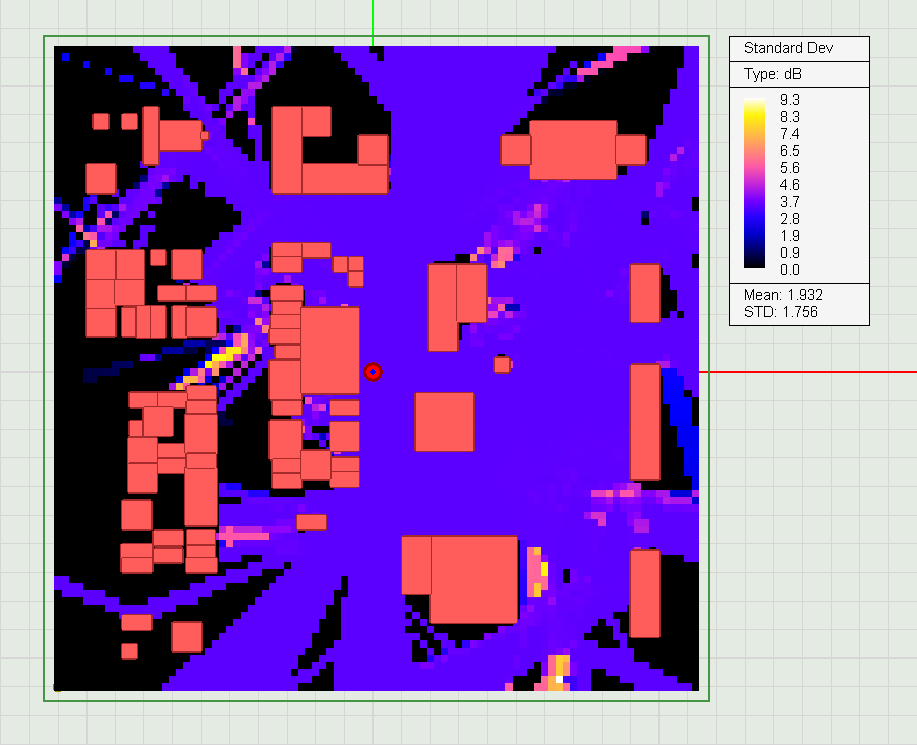

EM.CUBE's coverage maps display the received power at the location of all the receivers. The receivers together from a set/ensemble, which might be uniformly spaced or distributed across the propagation scene or may consist of randomly scattered radiators. Every coverage map shows the Mean and Standard Deviation of the received power for all the receivers involved. These information are displayed at the bottom of the coverage map's legend box and are expressed in dB.

In the Propagation Module, when you ran a sweep simulation (frequency, transmitter or parametric), you also have the option to generate two additional coverage maps: one for the mean of all the individual sample coverage maps and another for their standard deviation. To do so, in the Run Dialog, check the box labeled "Create Mean and Standard Deviation Coverage Maps". Note that the mean and standard deviation values displayed on the individual coverage maps correspond to the spatial statistics of the receivers in the scene, while the mean and standard deviation coverage maps correspond to frequency, transmitter or variable sets defined for the sweep simulation. Also, note that both of the mean and standard deviation coverage maps have their own spatial mean and standard deviation values expressed in dB at the bottom of their legend box.

The mean coverage map at the end of a transmitter sweep.

The standard deviation coverage map at the end of a transmitter sweep.

Â